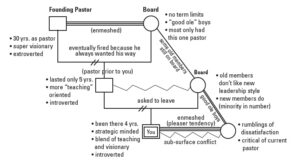

Many pastors begin a new assignment and get blindsided from issues they never expected. When that happens, it can be deadly. I’ve found that creating a genogram of your church, called a family diagram in psychology, can yield much insight into how people may have perpetuated unhealthy patterns in a church. It’s simply taking a bird’s eye view of your church’s past, looking for connections, and drawing them out. I excerpted below a section from one of my books, People Pleasing Pastors: Avoiding the Pitfalls of Approval Motivated Leadership that illustrates the process.

I wish I had known about family diagrams before I began to pastor. If I had seen how dysfunctional batons pass from one leader or significant stakeholder to the next, I could have avoided a lot of grief— or least prepared myself to handle those issues better.

I recall one church I served where the founding pastor had been a father figure to many of the early members. He was “larger than life” from both the stage and in one-on-one relationships. Because many of the old-timers had come to faith through his ministry, most had never seen any other pastor lead. He had become close friends with many of the stakeholders, making himself available to them 24-7. The father figure he played loomed large.

When I arrived as senior pastor, my leadership style was not to give people 24-7 availability, except in emergencies, because I’d soon burn out if I did. I was also a ready-aim-fire leader, whereas he was known as a fire-fire-fire leader.

After about a year, I began to sense a weird vibe from some of the stakeholder leaders. It seemed that I couldn’t please them, no matter what I did. I felt befuddled. But as a clearer picture of the previous pastor emerged, I began to understand what fueled this tension. I realized that some leaders wanted the best parts of him— in me. They wanted a father figure who was available 24-7. One leader even confessed to me that he expected me to be a father to him.

They also loved his larger-than-life dreams that seemed to come “straight from the Holy Spirit.” It excited them, and many felt that church should be perpetually exciting. My vision, however, came more slowly through a more deliberate and thoughtful process, definitely not eliciting as much initial excitement as his did.

They had transferred the idealized former pastor’s strengths onto me, and I had failed to meet those expectations. Edwin Friedman captured this transference when he noted, “Institutions . . . tend to institutionalize the pathology, or the genius, of the founding families.” [Edwin H. Friedman, A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix (Bethesda, MD: Friedman Estate, 1999), p. 199]

This founding pastor had left under difficult circumstances. As a result I also bumped into another unspoken script: a fear and distrust of strong pastoral leadership among some stakeholder leaders. Had I known how churches, like families, pass down dysfunctions, I could have better navigated those bumps.

If you’re a senior pastor, I encourage you to probe your church’s past to learn the hidden scripts against which you may be bumping. Take some key leaders and long-term members out to lunch and ask about the church’s history. Listen especially to the stories from the old-timers. The more you learn about your church’s past, the better you’ll respond to its dysfunctions. I’ve listed some questions below that you might ask these leaders to help you create a diagram.

- What significant events, both successes and traumas, have marked your church’s history?

- How has your church responded to traumas and crises?

- What problems seem to recur in your church?

- Does your church have any deep, dark secrets?

- How did the church begin?

- Was it from a church split?

- Was it a plant from another church?

- Are relatives of the founding families still in the church?

- Are some of the founding members still in places of influence?

- How long have pastors stayed?

- What were the circumstances behind their departures?

- How were their departures handled? How do people talk about the prior pastors?

- Is there an ongoing pattern of firing staff?

- Have any recurring sins persisted in staff or key leaders (sexual immorality, financial malfeasance, gossip and so on)?

You’re likely to find some repeating patterns. Simply knowing what you’re up against and paying attention to these multigenerational dynamics can give you a head start in dealing with the patterns. While acknowledging the past, you can more wisely lead your church into the future, knowing that these past patterns still play a part in the present. As Pete Scazzero has often said, “To go forward, you must go back.”

Here’s a fictional example of how someone might loosely diagram a church’s dynamics going back several years or several pastors. (People Pleasing Pastors by Charles Stone, permission granted, InterVarsity Press, 2014). Click on the image so you can see it clearly.

What impact have you seen that your church’s past has had on your ministry?

Related posts:

Pingback: Weekend Leadership Roundup - Hope's Reason